When something goes wrong on a project, your first instinct may be to apologize to your client, whether the fault is yours, or not.

Offering an apology to your client when something goes wrong on a project is a normal, healthy response. But, at the same time, you may be wondering if your polite behaviour might put you in a bad position somewhere down the road, in the event of an insurance claim and/or legal dispute. An attendee at our May 2021 Managing Risk virtual presentation may have had this in mind when they asked us to comment on an obscure piece of legislation called the Apology Act, 2009 (the “Act”). We are grateful to the attendee for raising this issue, because it’s something that every architect should know about. The Act itself is brief and its effect on possible liability seems simple and straightforward [see sidebar], but there is much devilry in the details, and exceptions to the law are many and varied.

So, however close your relationship with your client may be, and however benign your intent, heed this urgent piece of advice: Before you apologize to your client for anything, think about it and consult your lawyer and/or insurer.

The Act is premised on the idea that an apology can be a powerful tool. In professional practice, a timely apology may not be just an act of courtesy1; it may also go some way toward maintaining or repairing relationships2 and protecting your reputation. In the event that a legal dispute arises, an apology can often facilitate settlement and decrease litigation times.3

OFFERING AN APOLOGY TO YOUR CLIENT WHEN SOMETHING GOES WRONG IS A NORMAL, HEALTHY RESPONSE. BUT, AT THE SAME TIME, YOU MAY BE WONDERING IF YOUR POLITE BEHAVIOUR MIGHT PUT YOU IN A BAD POSITION SOMEWHERE DOWN THE ROAD.

If the Apology Act, 2009 did not exist, wise architects might be correct in assuming that any apology could be used as evidence of an admission of liability, and would be reluctant to apologize under any circumstances.

Although the Act helps to alleviate these concerns, it contains a number of significant exemptions to its application, and should not be regarded as a cure-all…under any circumstances. The Act does not apply in

criminal proceedings, or provincial offence proceedings,4 which cover a broad range of offenses. These include, quoting the Act, “charges for violation of the Occupational Health & Safety Act, Environmental Protection Act, Building Code Act, municipal by-laws, or other similar matters.”

The Act also does not apply if an apology is made while testifying at a civil proceeding in court or during an out of court examination5 – although there are exemptions to this exemption.6 Lastly, the Act does not apply for the purposes of section 13 of the Limitations Act, 2002,7 regarding a “claim for a payment of a liquidated sum, the recovery of personal property, the enforcement of a charge on personal property or [relief therefrom]”.8

In such cases, an apology would start – or restart – the claim limitation period. In addition, while the Act protects against the use of an apology – or statements of regret or sorrow – as evidence of an admission of liability, if the apology or statement at issue includes an express admission of liability, then that express admission may well be used as evidence in a civil proceeding. The Act defines an apology as:

…an expression of sympathy or regret, a statement that a person is sorry or any other words or actions indicating contrition or commiseration, whether or not the words or actions admit fault or liability or imply an admission of fault or liability in connection with the matter to which the words or actions relate.

Unfortunately, the courts may have difficulty determining whether any statement is in fact an apology under this definition. After undertaking a “contextual analysis” to determine which parts of the apology are admissible,9 there may still be some confusion. Elements of the apology that constitute “statements of regret” or the like will not be admissible; however, any admissions of material facts (or facts from which liability can be inferred), or express admissions of liability may be admissible. For example, if you say you are sorry that a problem has occurred, that statement cannot be used against you in a civil proceeding. But if, at the same time, or in the same correspondence, you make a statement about the suspected cause of the problem, that statement will be allowed as evidence. As a result, both oral and written apologies must be very carefully considered in order to avoid falling outside of the protections of the Act.

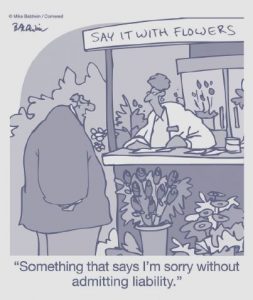

That is not to say that architects ought to remain silent or ignore potential problems as they arise. Such an approach would not do much to advance or maintain client relations. So how can architects express regret without implicating themselves?

Architects can tell the client that they are sorry about the situation, and otherwise demonstrate sympathy or regret, but must be careful not to accept or admit responsibility for the problem. In fact, where appropriate, the apology should be worded with a reservation that expressly denies liability. It is also important to avoid making any statements or admissions regarding the existence, cause or scope of the problem, which the client may feel is greater than it truly is. Further, the architect should avoid making any promises to make amends or repair any harm, whether through payment or other means, since this may be construed as an admission of legal liability.

BILL 108 2009: An Act respecting apologies

Definition

In this Act,

1. “apology” means an expression of sympathy or regret, a statement that a person is sorry or any other words or actions indicating contrition or commiseration, whether or not the words or actions admit fault or liability or imply an admission of fault or liability in connection with the matter to which the words or actions relate.

2. Effect of apology on liability

(1) An apology made by or on behalf of a person in connection with any matter,

(a) does not, in law, constitute an express or implied admission of fault or liability by the person in connection with that matter;

(b) does not, despite any wording to the contrary in any contract of insurance or indemnity and despite any other Act or law, void, impair or otherwise affect any insurance or indemnity coverage for any person in connection with that matter; and

(c) shall not be taken in to account in any determination of fault or liability in connection with that matter.

The architect may advise the client that it has put its insurer on notice, but should make clear that this has

been done out of an abundance of caution only, and that the architect does not accept or admit responsibility. These rules apply equally where the client suggests, or the architect suspects, that a subconsultant retained by the architect may be responsible for the issue. The architect is ultimately responsible for the contract with the subconsultant, so by agreeing with the client or otherwise ascribing blame to the subconsultant, the architect will risk facing liability for whatever damages, delay or extra costs that have been caused by the subconsultant’s error.

The distinction between an apology and facts that can constitute an actual admission of liability is critical, not only when it comes to ensuring the architect maintains the protection of the Act, but also to ensure that the architect does not compromise their professional liability insurance coverage, which requires that the architect must not take any action that would prejudice the insurer’s ability to defend the architect. This exclusion applies even if the architect believes that it could be responsible, or partly responsible, for the problem.

When problems arise, a sincere and heartfelt apology can go a long way toward maintaining or repairing a client relationship. Sharing an expression of regret, is generally the right thing to do. But to avoid prejudicing your rights, it must be done in the right way.

Contributing Author: Danielle Muise

Danielle Muise was called to the Ontario Bar in 2016 and is an associate in the Litigation Group at Aird & Berlis LLP. Her practice focuses on civil litigation, with an emphasis on corporate and commercial matters. She has acted in commercial, competition, construction, municipal, professional liability and real property matters. She regularly appears before the Superior Court of Justice, Court of Appeal, Divisional Court and Small Claims Court. She earned both her J.D. and her B.A. in International Relations from the University of Toronto.

Danielle can be reached at Aird Berlis LLP:

Brookfield Place, Suite 1800

181 Bay Street, Toronto, ON Canada M5J 2T3

T: 416.865.3963 E: dmuise@airdberlis.com

NOTES

1. The Act comes across as uniquely Canadian legislation, but in addition to other Canadian jurisdictions (all except Quebec), many US and Australian states have enacted similar legislation.4

2. Ontario, Legislative Assembly, Official Report of Debates, 39-1, No 71 (7 October 2008) at 3146. Members of the Legislative Assembly focused on relationships where trust is essential, for example doctor-patient relationships.

3. Ibid.

4. Apology Act, 2009, SO 2009, c 3, s 3 [Act]. Provincial offences being acts or omissions considered an offense under provincially enacted legislation. For example, speeding under the Highway Traffic Act.

5. Ibid at s 2(4).

6. The latter exemption would not apply to apologies made in without prejudice settlement discussions during the course of a civil proceeding, which are subject to settlement privilege.

7. SO 2002, c 24, Sched B.

8. Act, supra note 5 at s 4.

9. See, for example, Coles v. Takata Corp., 2016 ONSC 4885 and Cormack v. Chalmers, 2015 ONSC 5599.